Dear Readers,

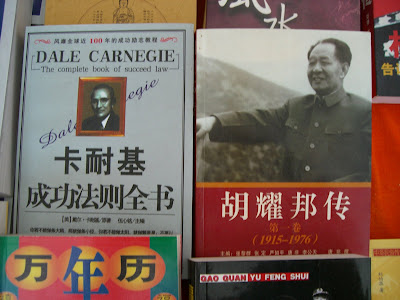

Dear Readers, My CBC colleague Yu Ying points out that the book pictured above is not a biography of Chairman Mao, but rather of Hu Yaobang. Ying writes, “I want to point out that that book in your photo was not a biography of Chairman Mao, but of Hu Yaobang. It looks like it is the first (focusing on his life from 1915-1976) of a series.”

I apologize. Since I don’t read Chinese characters, I am rendered essentially stupid in this culture. I naively looked at the Mao suit (which everyone wore) and the dates, which are about right for Mao, and just assumed it was the Great Chairman. I guess my stunning powers of observation are not always so insightful.

By the way: the picture of the mall in that same blog posting—it’s not

So who is Hu Yaobang? Since I have an internet connection, I can tell you a few things about him.

According to http://www.tiscali.co.uk/reference/encyclopaedia/hutchinson/m0018945.html,

“Hu, born into a peasant family in

From me:

Perhaps most importantly, it was Hu Yaobang’s death in April of 1989 that sparked the student protests leading to Tiananmen. There is a great discussion of this in Jan Wong’s Red China Blues: My Long March from Mao to Now, which Arienne and I have both read since arriving here. It’s a good read if you’re looking for something engaging on the Cultural Revolution, Tiananmen (she was there), and the rise of modern China.

Wong was surprised when student demonstrators began to mourn Hu’s death: “He was a political has-been….He was a buffoonish character who once advocated that Chinese, for sanitary reasons, use knives and forks instead of chopsticks. The joke went that Deng had chosen him because at four feed eight inches, Hu Yaobang was the only person on the ruling Politburo who looked up to Deng.”

So why, Wong asks, were the students rushing to memorialize Hu upon his death? She finds out that mourning Hu was the only way that the protesters could criticize Deng, who had purged Hu just two years earlier for being too permissive with student activists. “Within hours of his death,” Wong writes, “the students had adopted him as their fallen hero and were calling for a city-wide boycott of classes. A few days later, a million Beijingers joined in the biggest spontaneous anti-government demonstration in Communist Chinese history.” (Wong, 225-226)

So Hu Yaobang may have made a greater contribution to modern Chinese history after his death than during his life. What strikes me as odd is that the biography pictured above ends in 1976 before Hu became the Chair of the Communist Party during the 1980s.

Well, the contrast between Dale Carnegie and Mao would have been priceless, but don’t you still think it’s strange that Dale Carnegie and Hu Yaobang rest side by side in a gift shop at the

Thanks, Ying, for the correction.

Dave

1 comment:

Dave,

You're not getting your Colbert right. Never let facts interfere with truthiness. The truthiness of the original was the important thing.

Rob

Post a Comment