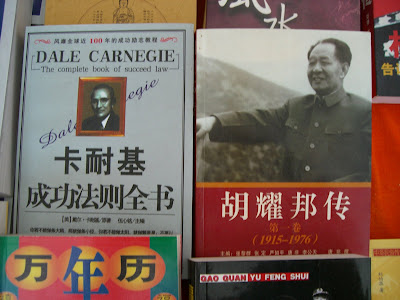

Two of my students slicing and dicing during their “cooking presentation,” which consisted of a lot of chopping and very little speaking. (See below)

One of the unintended consequences of coming to

I probably knew this somewhere deep-down, but now it's been made explicit. Me and grammar, for example, just don't get along. They should conduct comprehensive personality checks on grammar teachers before hiring, and if you are comfortable arguing both sides of an issue or exploring things from multiple perspectives, then you should not be allowed near a grammar classroom. You should be quarantined because you are like the black plague to the grammar body, which remains healthy on a study diet of blind acceptance of strict rules. I'm the kind of person who can always find exceptions to basic rules and who questions the "correct" answers given, wondering if there are alternatives. This is the wrong approach with introductory students who just need to learn the basic rules that they will be tested on. Critical thinking, or second guessing the book's prescriptions, is just not constructive to my students. There is a right and wrong answer and little room for discussion.

This is not to say that I don't do a good job in the classroom and that I'm not enthusiastic or funny or even, maybe, sometimes, inspiring. I try to be all those things, but deep down I'm not thrilled to be in a language classroom like I am in a history classroom. It would be like teaching at an elementary school: I really could do it but I wouldn't be excited about it for much the same reasons that I'm not excited about teaching language: I don’t wake up in the mornings eager to explicate the difference between "infinitives and gerunds for uses and purposes," which is what I covered today.

Using humor is probably the most important way that I connect with my students at CBC. But it is very hard to translate my unique sense of humor (which many of my CBC students claim is marginal) to early language-learners. For one, my favorite types of humor in the classroom are dry--in fact, so dry that some would claim them to be a barren wasteland of humor. But nonetheless, I like to mix dry humor with a good deal of sarcasm and irony (oh, aren't I sophisticated). This mix of humor, which is so thrilling to about 5 out of every 45 of my CBC students, usually just falls flat here. This means that I am pushed to extremes, peddling ever more gaudy slapstick routines just to get a laugh (probably of embarrassment), while most of my students sit and stare with wrinkled foreheads wondering just exactly what the foreign teacher is up to now.

Today, for example, we were learning the names of various machines and then using those lovely infinitives and gerunds to describe the uses of these machines: "Robots are sometimes used to perform [infinitive] dangerous tasks." After defining robot, I claimed that I was indeed a robot, manufactured in

I really knew I wasn't cut out to be a language teacher when the "fun" days were the most excruciating. Example: Making the students prepare food while narrating--a lesson which my colleague, a former fourth-grade teacher from

But my students had a lot of fun (I think). And I learned a lot. What did I learn?

I learned that most of my Chinese students have grown up eating more fresh fruit and vegetables than my American students. If I gave a similar assignment in the States, it is doubtful that so many students would have carted bags of vegetables to class. Instead they would have been squirting processed cheese on Ritz crackers. Clearly, my Chinese students do not eat as many packaged foods as my students in

I also learned that most of my students--even girls—never learned to cook (similar to American students), a fact that sort of surprised me. I naively thought that most Chinese children probably did a lot of helping out in the kitchen. I don't know whether it is because they are little "emperors" and "empresses" (offspring of China's "one-child policy" which encourages already doting Chinese parents to spoil their children), or because they are "rich-kids" whose parents can afford to pay for their education at the IEC, but these guys were mostly not trained in the culinary arts.

Even so, they managed to put together some foods that, although simple, tasted great, and sounded even better. "The Volcano is Snowing," for instance, consists of a pile of diced tomatoes with sugar on top. "The Heroes Gather" is a bunch of cut up root vegetables (including one called "The Heart is Beautiful") with some vinegar and salt.

Others were not as poetic: "Edible Fungus," "Edible Seaweed Soup," and "Bitter Scallion and Bland Noodles."

Ok, so in the end, it was actually pretty fun. I'm glad we did it.

Language lessons aside, interacting with my students is really a pleasure. They all come to class. They are all attentive (most the time). And they are really nice people. I'm told that our students in the

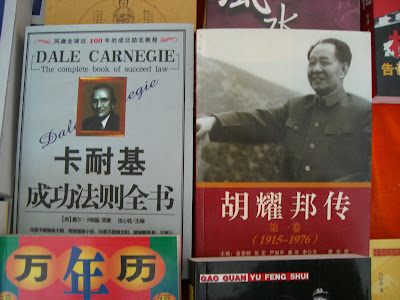

Straining to see the chopping presentations over banks of computer monitors. This is my only class that meets in a computer lab, which is not the best environment for anything but a computer class. These guys are actually “Network” majors, meaning that their English proficiency is even lower than my HR (Human Resources) and Travel majors. But they are one of the nicest groups of students you could have.

By the way, I’m also teaching seminars to faculty on American history and education, and those classes are more intellectually stimulating. More on that later.

Thanks for reading.

Dave